Object classification#

What is classification?#

Simply put, phenotypic classification is about categorizing objects into different groups based on their features (aka measurements).

📏 How do I measure it?

Phenotypic classification can be performed a few different ways. One way to break this down is by unsupervised vs. supervised classification.

In supervised classification, a human also provides information on what the different groups of objects should look like by providing representative examples of each group in a training dataset. The computer then learns how to assign objects to groups based on their measurements by testing models against the ground truth training dataset.

For example, you could classify cells based on a visual phenotype and train a machine learning classifier to derive which measurement ranges are associated with different classes. This is supervised classification because a person is providing instruction of how many classes there should be and examples of what each class should look like for the computer to learn from. An example of this could be annotating a subset of cells that are in different stages of mitosis and training a classifier to use your labels to find other cells in those stages.

In unsupervised classification, you group objects based on their measurements, but without any top-down human-defined guidance into how many groups there are or what the groups should look like.

For example, you could measure hundreds or thousands of features of cells from many treatments, as is typical in large-scale cell profiling experiments. Next you could let the computer cluster the cells into some number of different groups based on having similar measurements. This is a form of unsupervised clustering, where you observe what groups emerge from a computer considering their measurements only, and not class labels we impose as researchers. These sorts of clustering experiments can provide novel results but may also be harder to interpret; see this protocol23 for more information.

⚠️ Where can things go wrong?

Valid measurements are still important Classification can be simple or complex, but results always depend on the validity of your measurements. For this reason, all the caveats of earlier measurement sections also apply here.

Machines are lazy Machine learning classifiers aren’t necessarily going to learn the biologically relevant features that distinguish objects from distinct groups. Confounding features, or features that vary with your phenotype but are not biologically related to it, can limit the usefulness of your classifier and lead to incorrect conclusions. For instance, if clinicians often put rulers next to malignant looking moles and not next to benign moles and try to train a machine learning classifier to distinguish malignant vs. benign, the model might learn to classify images with rulers as malignant without tapping into any of the relevant features of the moles. This is a real example 24. If possible, examining which features your model is relying on to classify objects can be a way to check for this. It’s also important to standardize how you capture images of your different classes of objects and include a large enough training set with images with lots of variation. You wouldn’t want all your positive cells to come from samples you imaged in March and all your negative cells from samples you imaged in January, for example.

Violating model assumptions If using a machine learning classifier, different models come with different baked-in assumptions. If you’re starting out, it can be difficult to know which to pick. There are interactive tools such as CellProfiler Analyst 25 and Piximi that make training a classifier easier, especially if you don’t know how to code.

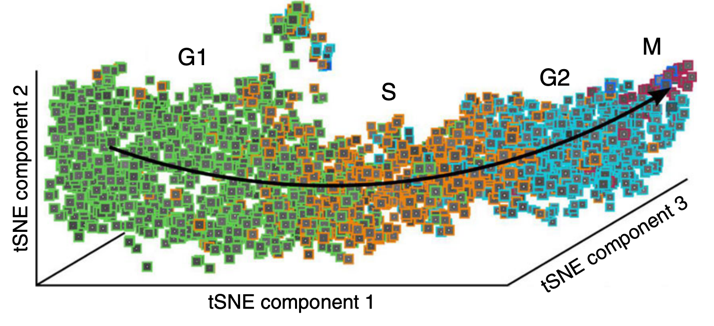

Messy boundaries Most methods of supervised classification, where the user assigns objects to a score or to a bin, ultimately treat each bin as a totally separate entity; biology is rarely so neat. For example, a supervised classifier for cell cycle phase must assign a cell to one phase, but in fact progression through the cell cycle is not a perfectly switch-like process, as can be visualized by measurements of individual cells (colored by their class given by a human observer). More sophisticated methods may be needed to classify more continuous phenotypes

Fig. 7 Strict division into supervised classes can be tricky for continuous biological processes. Adapted from Eulenberg, P., Köhler, N., Blasi, T. et al. Reconstructing cell cycle and disease progression using deep learning. Nat Commun 8, 463 (2017) 26#

📚🤷♀️ Where can I learn more?

📄 Data-analysis strategies for image-based cell profiling 27

📄 Scoring diverse cellular morphologies in image-based screens with iterative feedback and machine learning 28

🎥 iBiology video series: Measurement and Phenotype Classification

📄 Interpreting Image-based Profiles using Similarity Clustering and Single-Cell Visualization 23